|

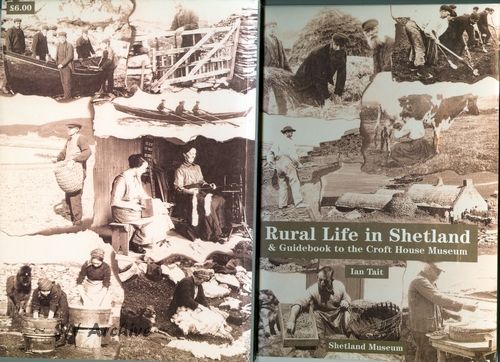

Rural Life in Shetland & Guidebook to the Croft House Museum Ian Tait, Shetland Museum, GB, 2000 |

There are 4 photos of dogs in this booklet: One photo each on the front & back cover, which probably shows the same dark brown white herding dog, but which I think is at least 45-50 cm tall. On page 56 there is a photo of fishermen with a very (modern) Border Collie like dog (also not small). Only page 14 shows in the photo "Setting up kols of hay in a Bressay meadow aroung 1900" a black and white (piebald) small dog, which could well be a "Shetland Collie" of that time.

There are 4 photos of dogs in this booklet: One photo each on the front & back cover, which probably shows the same dark brown white herding dog, but which I think is at least 45-50 cm tall. On page 56 there is a photo of fishermen with a very (modern) Border Collie like dog (also not small). Only page 14 shows in the photo "Setting up kols of hay in a Bressay meadow aroung 1900" a black and white (piebald) small dog, which could well be a "Shetland Collie" of that time.

Page 1: "RURAL LIFE IN SHETLAND

AGRICULTURAL LANDSCAPE

The landscape of Shetland in the 19th century was one dominated by agriculture. ... Most people belonged to an agricultural, or crofting, family, and there was much more of a dependence on the land and sea by the population as a whole. The situation of the farms, the organisation of land into arable and non-arable areas, and the inter-relationship between townships was basically a medieval system. This system governed the way people lived their lives, as much of the work was done communally. Farms were located wherever there was cultivable land, also boat landing-places, and to a lesser extent, water and fuel. ...

The land was divided into infield and outfield, or toun and scattald. The toun was enclosed by a hill-dyke, the toun land containing a single croft or, more commonly, a group, of say six. The positioning of each croft within the toun was typically one of an older cluster of around three farms, ... . The function of the toun was the area where crops were raised and fodder grown, in the summer, whilst animals were living out in the scattald (common hill-land). The arable ground, on which the crops were grown, was managed by a system called riggarendal. By this arrangement a proportion of good and poor land was allocated to all within the toun. ... everybody's arable land was not all near their own house. The grass meadows, ... was shared out between the crofts, depending on the number of animals they kept. In winter, the animals, which had been living on the hills, were allowed back into the toun, and could graze on the grassland there. ... The scattald was the hill land, outwith the hill dykes. This land was the summer pasture for cattle, sheep and swine. It was the place where peats were cut, turfs or roofing, etc., rushes for ropemaking were harvested, peat mould scraped for animal bedding, heather for ropes and fodder. The scattald was a common land to all those within the toun, ..."

Page 3-6: "Livestock

The most important animals on the croft were the cattle. ... The cattle kept were the native breed, not common today. They could be black and white, roan, speckled, etc., were very small, and had horns. Cattle were important as the principal source of milk, as a source of muck for fertilising the land; as oxen they were used as draught animals, and when slaughtered the meat, hides and horns were all used. The cattle were kept in a byre, the interconnecting doors of house and outhouses enabled easy visits to tend animals in all weathers. The cattle were kept in the byre all nights of the year. Besides protecting the beasts from the cold at night, the keeping in of the cattle was done principally to save their muck. ...

Sheep were kept for two primary purposes; for their wool for making clothing, and their flesh for food. The native breed of sheep had characteristics making them suitable for the climate; they were hardy, could survive on meagre fodder, could survive being snowed-under, and were long-lived. They were able to lamb themselves without assistance, and the ewes were better mothers than other breeds. Their wool was very fine and soft, and when spun made very warm knitted or woven goods. The sheep were notable for their variety of colours; black, brown, grey, white, white, plus a variety of patterns. Ewes had horns, the rams often having four, or (rarely) six. These sheep were very nimble and could access crags to graze, which could cause difficulty at sheep-driving time. Because the Shetland sheep were notorious for their ability to jump fences, many measures on the croft had to be taken to keep them out of crops. In the eighteenth century, hill-dykes tended to be more inferior, and more reliance was made on the 'pund', a circular enclosure in which sheep were kept overnight, sometimes for milking the next day. During daytime, dogs would stop sheep straying onto crops. By the 1870's this practice was all but extinct, and hill dykes were well built-up. ... Some sheep adept at getting through these fences had wooden checks fitted around their necks to hinder them climbing through. ... When sheep were being pastured on toun land and crops were still growing they had to be tethered. Because they were hardy, sheep lived outside all year round, but lamps over-wintered in a lambhouse. Because everyone's sheep existed together on the scattald, a means of identification was necessary to tell who was the owner of particular sheep in the flock. Ears were marked with yarn ..., then finally an incision was made in one or both ears. Because sheep are territorial, they generally didn't stray far into distant scattalds. The 'caa' was the annual sheep driving in which the community within the one toun herded, with the aid of dogs, the flock into the krø (a circular or rectangular stone enclosure, with a gate). Here, the wool was plucked off, taking advantage of the sheep's own natural moulting of its fleece. Rams were often kept on offshore holms. ...

Every croft kept one pig, all the crofts in the toun releasing them to live on the scattald. The native Shetland breed is now extinct. It was small and had stiff black bristles, plus tusks. These swine lived on worms, roots, etc., in the hill, and like the sheep were taken inside the hill dyke in winter. However, the pig stayed indoors during the winter months, ..."

Pages 33-34, 36: "CHANGES TO CROFTING LIFE AFTER THE 1870s

Since medieval times, changes to farming life in Shetland had been slow and gradual. In the 19th century, changes were more radical (indeed even more so after the turn of the 20th century). These changes affected diverse aspects of the crofting life: ... the way the land was divided up, the pattern of cultivation, the method of enclosing the land, the types of crops grown and livestock kept. The economy changed, as more people worked for paid employment, their wages importing manufactured good into the household. As a whole, the people's quallity of life improved.

In the 1870's, the population of Shetland was around its peak. The number of people had grown to such an extent that land which was barely viable for supporting a croft was broken out for cultivation. ...

..., this being largely due to the fact that many landlords kept as many tenants as they could, so that he could employ more fisherman. As part of the crofter's tenure they had to fish for the landlord or 'laird', or face eviction. The number of people rose, despite the conflicting policy of some other landlords, who evicted crofters from their homes, and made the township into sheep farms. At the same time as the crofters were obliged to fish for one 'laird', and not be allowed to seek a better price from other fishbuyers, they were kept in another form of bondage by merchants.

Merchants accepted croft produce as payment for shop-bought, but at the merchant's own value. Therefore, the crofters were kept in permanent debt to the traders. Because of these oppressions, Parliament passed the Truck Act and Crofters' Act in the 1870' and '80's. This now freed people from the threat of eviction, the power of the 'lairds' to create sheep farms war curtailed, rents could not be increased, etc. After the 1880's the largest change was the cessation of change. No longer were there radical 'improvements' by land owners, and the people had the freedom to fish for whoever they chose. The period after the 1880's was at least, for a time, one of stabilisation for the crofters. Parallel with this was the developement of the herring fishing, from the 1870's on.

By abandoning the traditional line fishing, and getting work on herring drifters or on cod smacks, money came into thousands of Shetlands households. This, in fact, allowed fishing communities to grow, the people there having no need for crofts. ... during the late 19th century the merchant marine was the principal employ for crofters wishing to gain paid employment. Of course, these same men praticipated in the everyday running of the croft when home in Shetland.

... The majority of landowners, and a good many crofters too, saw the medieval system of working the arable land as archaic, wasteful and inefficient. ...

By the late 20th century, many more changes have occurred, ... Especially after the 1939-45 War, new opportunities opened up for Shetlanders to obtain paid employment. Antarctic whaling, weaving, knitting, fishing, etc. This meant people no longer had to, or indeed could in a consumer age, survive on a croft. ... As the same time as the population is polarising into crofters and non-crofters, vast tracts of formerly arable land has fallen to sheep pasture.

... In the 1890's for every one person in Shetland there was one cow, and three sheep. In the 1990's for every one person there was only a quarter of a cow, but a remarkable eighteen sheep."

Page 49: "The Barn

... Besides farming equipment being kept in the barn, fishing gear was also stored. ... On the twartbaks [= long battens] you can see a herring net and line buoy, which is made from the skin and tarred: Both sheep's and dog's skins were used for making these.

The Stable

Most small Shetland farm steadings did not have a stable. Although the small native Shetland horses were weidely used for harrowing, ploughing, carting, and flittin [= transporting], they spent most of the year free on the scattald. Horses were moved into the stable in winter, such small stables ... holding one or two horses."

If you discover any errors in the text that may have been caused by the transcription, please let us know for a prompt correction.